When your Dad had to dismantle and move the school to another part of the village, why did he do it?

The school was in the center of town, there was a street on each side, of businesses. On one side it was ashes, bombed out, and the other side too, because the Japanese soldiers had a practice fire drill, to put out a fire, and lost control. All burned. I remember finding a box of burnt staples. After the war we came back from the rainforest, with the natives peoples, and some Chinese people lived up river. We had to move the school because they were rebuilding the town. The government said. So they wanted to develop the town and they gave my father a plot of land to move the school to.

You know, it was all wood houses then. I remember it in pieces, looking out my window. Outside of the window was a lime tree, the small limes you get in the tropical, like ping pongs. my father would put nails in the trunk, the cook gave me nails and would get me to help her put nails in. You know, citric trees need iron, so later when I lived here I saw that fertilizer had iron in it! I was looking for limes on the ground, and I looked up, and there was a green snake right there, very close, just staring at me, right in front of me on the branch. Those tropical snakes are very poisonous, this are called green arrow snakes.

We had to use gas lamps, you know, kerosene, the type with gas in it, and you light it on fire to see, well I was walking on the path and there was a black and white snake, dangerous, and my father pulled me behind him, just grabbed me and threw me, and killed the snake. I don’t know what he used, but he did.

It’s not like my father did it all himself you know, he had help, the people helped, the Chinese people. You know the government didn’t care about Chinese people. The roof was wood slats, it was a roof all full of little wood planks, and they would take them down and bundle them up. There were no cars then, so they used bull carts. They built the classroom first, the smaller building, that’s were we lived while the others were being built. Then the second, the third, and main house, and the kitchen. They built a covered walk from the kitchen to the main house. The three classrooms/ buildings were moved and build then we move into those. Then the main big building were taken apart, very organized and marked in the different piles of timber. It was exciting for kids to watch and to be shouted for getting too close to the building site.

They were friends, my father and the headman. I remember in the headman’s quarters the divisions are all made of mats. There was a big net on one side full of skulls. My dad told me not to be scared. The Japanese when they come to the forest walk in a single line, and the natives hide in the tall grass, they would just grab off the last one and take his skull. On September 2nd the Japanese officially signed on the the warship Missouri signed the end of World War II. The Australians came and bombed too, against the Japanese. We were near Brunei, which was rich, made gas, so they fought over it. They surrendered I think in 1945.

Bintulu was just a small fishing village, so they wanted to keep up appearances. The school was in the center and both side burned to the ground, so people had no choice but to flee, they had nowhere to live. We lived with the natives for about must have been a year. There are Sea Dayak, and Land Dayak. They came down when they heard that the Chinese houses had burned down and invited us to live with them. The men wore loin cloths, and the women were bare chested. They would come down to trade, wild boar, chicken, birds, sago for salt, flour ,sugar, and cloth too. The relationship was good, the Chinese merchants let them stay under the overhang of the houses so they would have a place to sleep for their long journey. They made this butter, out of fruit seeds, they grind them and let the oil coagulate in bamboo, oh I loved that so much, I would always ask for it, just eat it with some rice.

We went to a rubber plantation first, the Japanese were machine gunning and started to bomb to prevent the Chinese from running away. Then we went to the long house.

When we all went back into town, to the school, the floor was full of animal bones, covered in these white bones everywhere. The Japanese soldiers ate everything, all the animals, dogs, they didn’t have anything to eat. All the furniture was chopped up for fire.

– Excerpts from conversation with Mom, Ivy Chieng-Ping Su. September 2020. Events are surrounding the Japanese occupation of British Borneo, Dec 16 1941- Sept 12 1945.

copper, horse hide, steel

95 x 48 x 30in / 242 x 122 x76cm

right: fig 27.3 ghost

Ceramic, ceramic tiles, steel, acrylic enamel

16 x 12 x 33in / 41 x 31 x 84cm

Ceramic, ceramic tiles, steel, acrylic enamel

16 x 12 x 33in / 41 x 31 x 84cm

steel, gold-plated steel, acrylic enamel, cement

41 x 28 x 3-1/2 in / 104 x 71 x 9cm

ceramic

10 x 3.5 x 2in/ 25.5 x 9 x 5cm

ceramic, graphite

20 x 14 x 17cm / 8 x 5.5 x 6.5in

steel, brass plated steel chain, unfired black clay

75 x 6.5 x 5.5in / 190 x 17 x 14cm

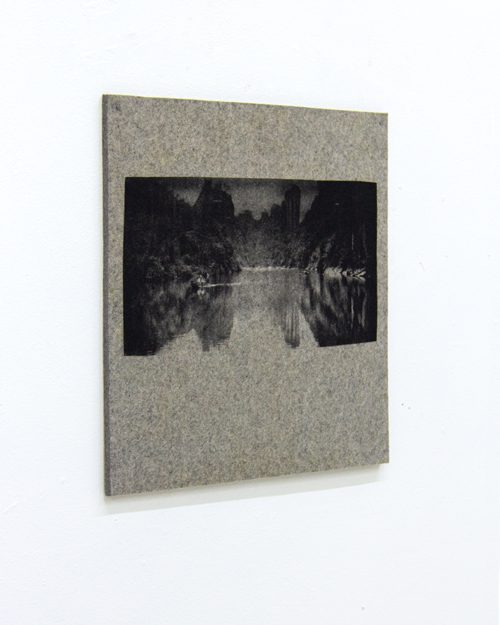

screenprint on wool felt

Edition of 5

16-1/2 x 16-1/2 x 3/8in / 42 x 42 x 1cm

copper, horse hide, steel

95 x 48 x 30in / 242 x 122 x76cm